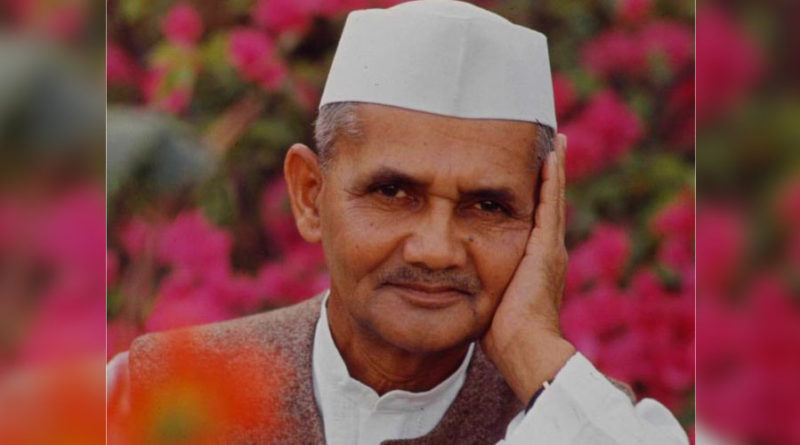

People loved Lal Bahadur Shastri who, in a short period, had won everyone’s heart and respect with his honesty, sincerity and passionate dedication to serve the downtrodden. He not only brought back the lost glory by winning the war but rekindled the pride of forgotten people, specially, farmers. People were fully aware that he didn’t even have the money to buy a personal car and for which he had to take loan from a bank. While Nehru’s era was engulfed with corruption, Shastri showed a humble way of life based on tyaga.

After his mysterious death in Tashkent, obituaries poured in from all over the world which reflected the respect he garnered in such a short time. “Lal Bahadur Shastri died at a pinnacle of popularity that no one in India believed possible when he succeeded the late Jawaharlal Nehru as Prime Minister barely nineteen months ago,’ reported the New York Times.

It was said that “Nehru died too late, for Shastri death came too early”. Though it is believed that his popularity had soared because of his response to the war with Pakistan. But he made unprecedented reforms in the economy. It won’t be wrong to say that he was India’s first economic reformer. Though he was expected to follow Nehruvian economics of emphasis on physical controls instead of prices, the focus on industry instead of agriculture and the crushing web of controls, he realised that it was proving hostile to national development. In a very quick time, Shastri dismantled it piece by piece. He pumped in fresh thinking into India’s development strategy. People understood that Shastri wore no ideological blinkers and, instead, he saw facts as they were in reality and how they can be tackled with practical solutions to help the downtrodden. Unlike Nehru, he went about his job in a quiet manner, without any showmanship.

Myron Weiner, professor in Political Science at M.I.T., praised Shastri’s policies to improve Indian agriculture and to increase production of consumer goods. Shastri’s growing dependence on the free market mechanism and removal of government control from the steel industry relieved many Indian economists and businessmen, Weiner said.

American ambassador to India, Galbraith said that Shastri’s ability to manage Indian affairs during “one of the most difficult periods in Indian history” was a “very considerable achievement.” He cited Shastri’s skill in dealing with India’s food and border problems and in substituting Hindi for English as the official language.

Shastri showed courage, conviction and gave hope to people. He was a symbol of Tyaga. He personified Hindu philosophy of ‘Sada Jeevan, uchch vichar.’

Shastri, in his personal life was very simple, against wastage of resources and fanatic about honesty in public life. As AICC general secretary, he used to give his wife Lalita ji a monthly allowance of Rs 40. When he came to know that she had managed to save Rs. 10 out of it, he felt he was overpaying her and cut ten rupees from her all allowance. Therefore, there remain legitimate grounds to speculate how the Indian economy would have developed had Shastri lived longer. India went on to adopt similar reform measures twenty-five years later, which put the economy on a higher growth trajectory. The little man was just way ahead of his times.

When Lal Bahadur appealed for a voluntary vrat, India was going through a food crisis. Shashtri used ‘tyaag’ as a political shashtra to address it besides sowing the seeds of a Green revolution. Politics needs optics. Optics which are ingrained in Indian ethos are always most effective. Vrat is part of Indian culture. Shastri used it to make a point about the food crisis. Nehru didn’t learn tyaag from Gandhi. Shastri did. How does a country transform? Only when the peoples make small sacrifices then can we transform. Tyaag is the highest quality. A door to shuddhi. Without shuddhi there is no transformation. A lot of media people and intellectuals, who were patronised by Nehru and became the beneficiaries of the seeping corruption, called Shastri’s call for ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ a political gimmick and a deviation from Nehruvian ideology. They didn’t want to sacrifice even one meal and instead intellectualised their lack of commitment to the national cause. But millions of Indians did fast on Sundays.

If we entrust our destiny in a leader’s hands, we must be prepared to be led by him on the path of change. If that path requires sacrifice then why shouldn’t the true followers be ready to sacrifice. If Bharat has to become truly independent then tyaag has to be mutual. Citizens must always choose tyaag based leadership over leaders with egos.

I believe I was destined to make a film on Lal Bahadur Shastri’s mysterious death. My young team went through unsurmountable difficulties and sacrifice and we faced immense opposition. But it was our ‘tyaag’ and ‘tapsya’ that brought us to this day, when for the first time in independent India, on 2nd October, a film other than Gandhi will be shown on national television – ‘The Tashkent Files’. What gives me immense satisfaction that children all over India will learn that 2nd October is not only Gandhi Jayanti but Lal Bahadur Shastri Jayanti also. What can be a more fitting tribute to this great ‘tyaagi’ son of the soil of India.