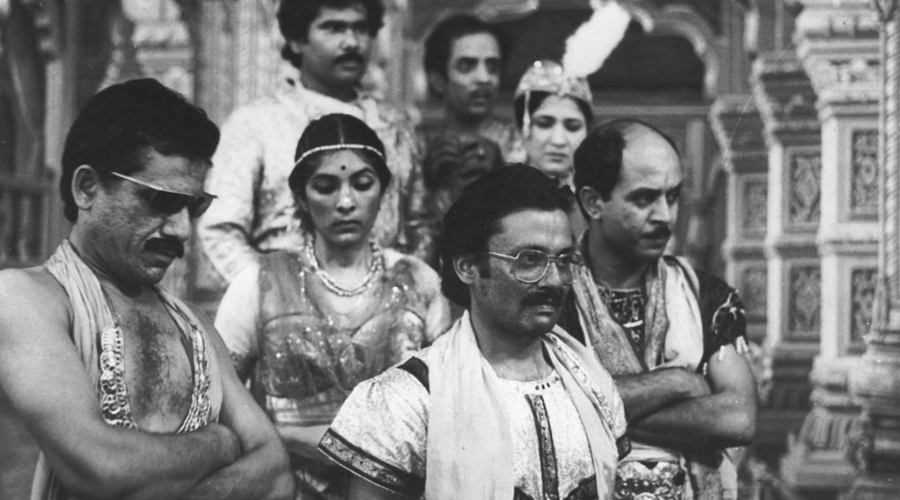

Nahari in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi, sub-inspector Anant Velankar in Ardh Satya and Ahuja in Jaane bhi Do Yaaron– Om Puri, the true actor and hero, etched his powerful story and presence in Indian cinema with these three unforgettable roles and characters.

Om Puri, the artiste and acting school, will never die.

In 1982, when Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi released, I saw it with my family on a Sunday, matinee show. Every good film shakes us, touches us, surprises us. Gandhi had all those qualities, but there wasn’t any surprise for me. Both my parents were freedom fighters and worked closely with Mahatma Gandhi. We grew up as semi-Gandhians, hence, we knew almost everything about Gandhi’s life. The film was emotional, exhilarating and inspiring. I was in awe of the scale and grandeur.

For me, the real moment of Gandhi came towards the end, and it surprised me when Nahari, a character, tells a stubborn Gandhi, “I’m going to hell. I killed a child! I smashed his head against a wall.” I had goosebumps.

As a student, I knew about the cruel and the barbaric face of communal violence, but this was the moment when I felt it. Never before and never after this, have I felt so disgusted, so frustrated and sad.

Few seconds later, in the same scene, Gandhi asks Nahari to adopt a Muslim child and raise him. I saw Nahari’s communal prejudices shattering and his human soul flower.

It was the second time, after Anand, that a character in a movie made me cry. The scene wasn’t about Nahari. It was about Gandhi. Nahari was just a device to elevate Gandhi’s greatness. But the actor who played Nahari made it belong to him. He packed the complexity of life, human behaviour and compulsions of communal society, hatred, violence, compassion, respect and obedience come alive, in a blink-and-miss scene, in a film crowded with some of the greatest actors.

I did not bother to find out the name of the junior actor who played Nahari. All I remembered – the eyes and voice of Nahari. The 60 seconds that I spent with Nihari made everything my parents had told me about the Partition seem real. I felt the pain of Partition. The hatred. The violence. Whenever there has been communal violence in India, the only image that comes to my mind has been of Nahari.

In 1983, like any other young student of India, worried about an uncertain future and angry about the present filled with corruption and injustice, in the phase of hopelessness, I came upon a film which haunts me even today. The film is Ardh Satya.

The film was running at Regal, at Connaught Place, New Delhi. I came out of the Khadi Gramodyog showroom and saw its poster. I paused. The hero was the same guy who played Nahari.

It took me no time to buy a ticket to Ardh Satya. I saw the movie in an almost empty hall. When you are alone in a cinema hall, the darkness becomes darker. In that darkness, Ardh Satya became ‘satya’ for me. The characters have stayed with me. I remember how angry, frustrated and hapless I felt, as the pain and complexities of sub-inspector Anant Velankar grew with each scene. I choked, as he recited the poetry Ardh Satya, to the character of Smita Patil. As he reads the poetry, its true meaning starts sinking in him. He starts relating with the dark reality of life as he recites each line… “Ek palde mein napunsakta, aur doosre palde par paurush, aur theek tarazoo ke kaante pe ardh satya. (On one hand is a coward, on the other – a man, and half truth – in the centre). Then, he chokes. The audience chokes. The gut-wrenching truth of human suffering comes upon the character and the audience, in real time. I have not seen such quality of controlled and experiential performance – before or after this moment.

If someone asks me to list 10 best moments of Hindi cinema, I will be utterly confused between Nahari’s confession in Gandhi, and this moment, from Ardh Satya. Velankar’s experience became my experience.

The climax, in Ardh Satya, is one of the finest we have seen in Hindi cinema. Not because of its cinematic treatment, but the nuanced, controlled and economical acting from Om Puri. When he says “… kya mein tera kutta ban jaaon…. Tera goo khaoon…,” I actually felt as if there was shit all over me.

When he strangles Sadashiv Amrapurkar’s antagonist, I felt what he did was exactly what I would have done. When Amarpurkar was dying, I was breathing again. I felt as if I was liberated. I didn’t know then, that decades later, I’ll base the climax of my film Buddha In A Traffic Jam loosely on the climax of Ardh Satya. The only major difference is that my hero kills the antagonist with his idea, instead of his hands.

When I look back today, I feel this was also one of the most difficult performances ever in our cinema. The character had no external support. There were no specific costumes to hide behind, no sets, or clever lighting to enhance the character, no supporting characters to infuse power in the character. And there was no background music to accentuate emotions and dramatised conflict. The director chose to leave the audience alone with the protagonist in a small place with hardly any space to manoeuvre. There was no exit.

Velankar strangled us, and finally, left our neck in the last minute, when we were left without any hope and made to feel defeated. I actually gasped for air. He made us feel how it feels to die, and when we inhale the air after two hours of choking, we realise what it means to be alive.

I have never had the courage to see this movie again. I thought I wasn’t equipped to take so much haplessness and anger. I didn’t even bother to know who made this film and who played sub- inspector Anant Velankar. I felt numb for months, like one would feel, after being strangulated for a long time.

Until, I came upon Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron. A madcap comedy with an ensemble cast. I didn’t know most of the actors, but one face attracted me. The same face had choked me in Gandhi and Ardh Satya. I was intrigued to find what this angry man was doing in a slapstick comedy.

Ahuja, in this film, was one of the most entertaining characters. The way my Velankar played a moneyed and alcoholic Punjabi, his heart on his sleeve, isn’t what I had ever seen in Hindi films. There is a famous scene in the film. A drunk Ahuja engages with DeMello, played by Satish Shah, in a coffin, in the middle of the road, and misunderstands it for a car. This is the funniest conversation in any film. What makes it a classic? Ahuja is talking to a corpse. The greatness of an actor is tested when he has to deliver inane dialogues which have no punch, no drama, no intensity, no layers and no emotions.

In my experience, actors get a bit shaky about such dialogues and want the writer to change them, or want the director to construct the scene in a certain manner, to cover up the “inane” dialogues. These are functional dilaogues.“Kitne aadmi thhe?” is a functional dialogue, but the way Amjad Khan infused life in it, it became not just a classic, but the most spoken dialogue ever. Similarly, in JBDY, the way Om Puri infused life in simple dialogue ‘… radiator bhi sahi hai… carburetor bhi sahi hai… are yeh to puncture hai…” or “… ek sharabi hi ek sharabi ko samajhta hai…” made this scene a classic.

The beauty of the scene is that the actor has no crutches. There is an empty road, a coffin and a corpse. He doesn’t depend on any external help, he is drunk and having a good time, indifferent to the entire world, and you feel so. It is his private moment where he is trying to help an imaginary car and any scene that comes close to it is Amitabh Bachchan’s self-talk with the mirror in Amar Akbar Anthony.

In a comedy, especially, slapstick, you have to be an actor of an exceptional quality, to make the most illogical scenes look real. The car scene with Satish Shah is one such scene. It stands on sheer acting prowess of this actor.

Nahari, Velankar and Ahuja. They were played by Om Puri. That night, when we were discussing the movie over drinks, I found myself telling a friend in Ahuja’s style “yaar, tu to puncture hai.” That night, I realised, I had become a student of the acting school called Om Puri.

Many movies and many years later, when I was casting for one of my TV serials, I decided to cast Om Puri. He had worked with my wife Pallavi Joshi in many movies, including, Susman, where he had played her father and always treated her like a daughter, which is why I had met him a few times with her. When I called him to fix an appointment he said “Tu kyon aayega bhai, mein aaoonga tere ghar… role to mujhe chaiye”. He walked to our house, in his shorts and a t-shirt. He listened quietly and then asked me, “To aap kaise chahte hain mein ise kaise play karoon?”

I just couldn’t believe that the man who had choked me once with anger and then with his comedy, and had made me his fan, was asking me how to play a role. Since then, I felt he was a family member. We couldn’t work then, but in my next film, he would have played the most important character. He is no more and I can never work with him. Maybe, I wasn’t capable to tell this master of acting “how to play a role”.

My last interaction with him was on a TV debate. We were sitting on the opposite sides on the Pakistan debate. He wasn’t in control and media knew about it. It angered me to see the media take advantage of his state by provoking him and misleading him to answer what he didn’t mean. I remember telling him on TV “Omji, I know you don’t mean what you say here.” I can vouch he didn’t mean anything he was condemned for.

Almost all his best performances were without much of cinematic support like power-punched dialogues, music, glamour or power or crutches like props, costumes or supporting actors. Yet, he made each character stand out on his own. The aloneness of his characters became his strength. Like his characters, in real life too, he had no support system. He was alone. In real life, it appears, he couldn’t deal with this aloneness and finally left us. The lines of Ardh Satya were prophetic. They describe best the conflict of Om Puri … aur theek tarazoo ke kaante pe, ardh satya.

After his funeral, I watched Ardh Satya again. I wasn’t scared. I wasn’t angry. I wasn’t saddened. In fact, I was happy after seeing it, I was liberated. I have learned that true artistes never die.